|

I've been so busy this summer that I haven't had a chance to write anything here since before I left for Mexico. My writer-in-residence program in San Miguel de Allende was more fun and productive than I ever imagined. I lived with two incredibly interesting writers in a mansion --really, a mansion--and we spent most days writing, some days teaching, many nights going out on the town, and many nights after that sprawled on one of our beds yakking and giggling like girlfriends who'd known each other for decades. I wrote five essays this summer, all of which are getting published soon, and my new book, Stolen Child, is coming out next week. (First review already out, in Publishers Weekly). So, yes, busy. Also, I've totally changed and fancied up my website so hardly use this blog anymore.

1 Comment

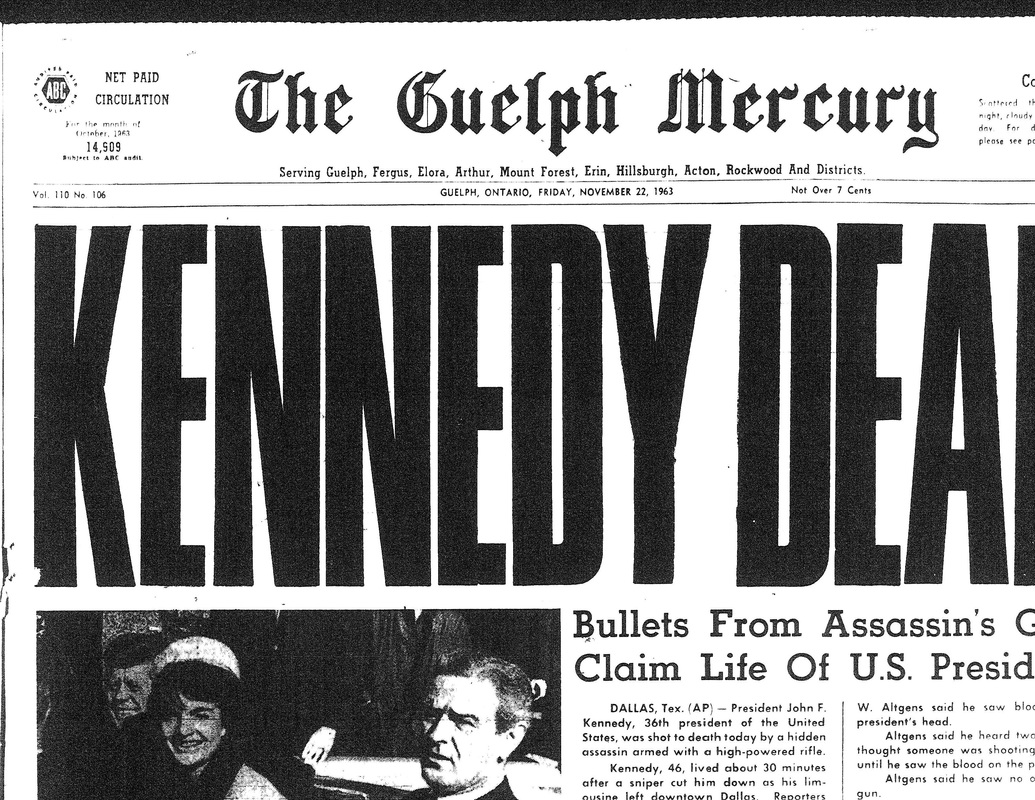

2016 Summer Writing Workshops 2016 Summer Writing Workshops I get to return to my old stomping ground of San Miguel de Allende this summer because I've been asked to be a writer in residence and teach a memoir writing course. When I was first invited I thought, huh? Mexico in July? That's the best time to be where I live in Wakefield, Quebec. I wait all year for July. I'm waiting for it right now. But then I found out that San Miguel is actually lush and green in the summer with desert flowers blooming and crazy rain storms blowing through every afternoon to liven things up. Maybe five weeks in San Miguel is just what I needed, I thought. Besides, it sounded like a great opportunity. So I said yes. The best part will be getting to sink my teeth more deeply than ever before into the art of memoir writing. I love teaching memoir. And I have a new memoir, Stolen Child, coming out in Canada and the U.S. in September. I am passionately interested in the qualities that make memoirs good and the qualities that make them, well, not so good. Here's my workshop description for San Miguel Literary Sala's Summer Writing Workshops The Art of Memoir and Travel Writing Workshop “Memoirs are held together by happenstance, theme, and (most powerfully) the sheer convincing poetry of a single person trying to make sense of the past.” Mary Karr Our lives are interlaced with stories: intriguing, fascinating, funny, tumultuous, sad, extraordinary, revelatory, heartfelt, and unique to each of us alone. This workshop offers you tools and insights from the master memoirists, as well as the instructor’s own experience writing three memoirs, to help transform the stories of your life into a literary work. Memoir writing isn’t writing your whole life. It is writing stories from life, from any time of your life—whether it’s the year you spent in a rocky relationship, your years growing up in a hardscrabble neighborhood, the road trip you took at 18 to search for your father, the Himalayan hiking adventure you finally embarked on when you turned 65—any story you feel is worth telling. Through discussions of specific topics about memoir and travel writing, and in-class exercises that are fun and thought-provoking, you’ll learn how to craft your stories into interesting and inspiring narratives. There will be assignments and you will be encouraged to share your work with the instructor and fellow participants for feedback. In a supportive environment, you’ll explore the creative doors that open as you commit your memories to paper. You have a story to tell, probably a lot of stories. The challenge is to find your way inside the story and bring it to life with fresh details that are unique to you. This course aims to help you find the keys. Workshop Information In this workshop you will learn that to be an effective memoir writer (which includes travel memoir) you must lead the reader directly into the time and place you’re describing, always remembering that your experience can only be conveyed through concrete original details. The more precise you can be in describing these details the more vivid a picture you paint in the reader’s mind. Through in-class exercises, you will work on portraying a physical reality that uses all the senses and exists in the time you’re writing about—a singular fascinating or terrifying place peopled with objects and characters the reader can believe in. Emotional stakes need to be set high—why is the writer passionate about delving into the past? In deciding what to write about: what haunts you? What are your obsessions? What stories never leave you? As for the writing itself, how can you make every single sentence more interesting, more alive, more lyrical and true? We will read excerpts from well-known memoirs and discuss what works—how the author actually brought a scene to life—and you will then try to employ these techniques in your own writing. For the travel writing section, we’ll discuss ‘finding’ the story and how this isn’t something you can anticipate before leaving; traveling for a story as opposed to traveling for travel’s sake; how to frame and craft your stories; how the ‘quest’ makes for a good travel story; the various types of travel writing; how to begin your stories to catch the reader’s (and an editor’s) attention, and tips on getting published in today’s rapidly changing market. The workshop aims to be inspiring, creative and most of all, fun. The ideal would be if each student could bring to the first three-hour class a piece they’ve been working on, or at the very least, an idea of what they’d like to work on, so we not only “break the ice” by getting to know each other, but the instructor and fellow participants can offer constructive advice. Click below for more on San Miguel.... All About San Miguel by Laurie Gough Ten Things You Probably Don't Know About San Miguel de Allende Note: For those of you thinking of starting a blog or website with weebly, don't! It is so glitchy that you feel like throwing something out the window. It won't even let me highlight the links above in colour, or add more pictures of San Miguel. Ahhh! I just heard that my hometown newspaper, The Guelph Mercury, which has been operating for 149 years—making it one of Canada’s oldest newspapers—will run its last issue ever this Friday. My multimedia-artist friend Dawn Matheson is organizing a “Guelph Mercury Hug Mob Goodbye” where the newspaper’s long-time readers will converge for a group hug of the old downtown Mercury building—and a group hug of the staff itself as they walk out of their jobs for good. All Guelph Mercury staff have lost their jobs. They had five days notice. (Who will cover this local story of the group hug, I have no idea, probably no one.)

So long Guelph Mercury, a newspaper my elderly mother still subscribes to, a newspaper I delivered as a kid, a newspaper which prided itself on being “intensely local” and committed to putting 25 stories and 75 local names in every issue. The Mercury is just another victim in the slow train wreck of print media, and the train’s name, as everyone knows, is the Internet Express. (I just made that up but I think it’s kind of catchy.) As a writer I see the fallout of print media’s demise every day. I feel lucky because at least I caught the tail end of making a living as a travel writer, a job that is pretty much archaic today. After getting two books published it dawned on me that some people were actually making a living publishing travel writing in newspapers. I thought I’d try this myself and was shocked when I hit it lucky with the very first story I ever submitted, an article on carpets in Morocco. The Globe and Mail actually paid me $1000 for the story and asked for more. I thought, like Mary Tyler Moore, I had made it. I had a real career. And for a while, I did. This was in the days when just the travel section of The Globe was twice as thick as the entire paper is today. It was when people were just starting to talk about the internet and only a few people I knew were actually “connected” to whatever it was that got you connected to the internet back then, phone lines mainly. Back then, the internet seemed to be kind of nerdy. But after a decade passed of my being a travel writer for newspapers and magazines it was all over. Nobody was paying money for travel stories anymore, certainly not cash-strapped newspapers, and only during that short dotcom bubble of the late 90s was I getting paid to write for websites. (Salon.com once gave me an incredible US$1500.00 for a single story, unheard of today.) So what does a writer do when nobody is paying for the written word anymore? She gives travel writing classes! She tells people how to become a travel writer! It’s all an impossible dream of course and I tell people that and you know what? They don’t seem to care. They don’t care because they still want to know what makes a good travel story, how to hook the reader with the first sentence, how to transform their gut-wrenching trek across the north of Spain into an actual story for their children and their friends. They don’t care about getting published—they can take a self-publishing workshop some day or write their own blog. Mostly, these people just want to write, to recall and record the events of their lives. And I’m so happy about that because writing is the best part of being a writer. (See: What Writing Gives Me) Some day, perhaps, when some cyber-destroying barbaric terrorist group unplugs us all and we’re left to wander outside and have actual conversations, the written word will still be there, quietly sitting on people’s dusty bookshelves or in their compost heaps, waiting to be picked up by someone’s hands and read, page by page, deep into the night.  Everyone knows that with the advance of the internet, a revolution has taken place in the way people travel. Most of us haven’t used a travel agent since the last century, and with sites like tripadvisor, you can ascertain from other travellers whether you want to take a chance on a place. Of course, the digital age also has its drawbacks while you’re on the road. Rarely now will the solo traveller have that exhilarating heady feeling of being wildly free and blissfully removed from the world. How could she when she’s holding her phone? But I digress. (And I hope I’m wrong about her phone.) Recently my husband Rob and our twelve-year-old son Quinn and I spent a month in Spain and Morocco. It’s not the first time we’ve pulled Quinn out of school to travel. We do it every year. But instead of taking a road trip in our camper van, or staying for several months in the same town in Mexico, this time we travelled the way I used to. We backpacked. We were on the road. We made our way from one town to the next, cramming ourselves into dilapidated buses, hurtling down dusty Moroccan roads, smiling at Berber nomads and sometimes staying at a villager’s house if invited. In Morocco, it was impossible not to have an adventure or enlivening encounter every waking hour. Having adventures in Morocco was familiar to me. And this time the adventures were often fuelled by Quinn kicking his soccer ball everywhere we walked, which inevitably led to passing strangers urging Quinn to kick the ball to them—leading to an impromptu game with more passers-by joining—which often serendipitously opened us up to new worlds of people. But something that was distinctly not familiar to my old backpacking days were workaway.info, airbnb.com, and blablacar.com. Those three websites transformed the nature of our trip. Every night in Spain, from Madrid to Seville to Barcelona, we stayed at airbnb’s. As long as we had wireless for our tablets (we don’t have a phone) we could plan as we went, booking airbnb’s a day or two ahead, whatever our freewheeling schedule allowed. Of all the airbnb’s we stayed at, only one was a dump. I took photos to prove it and airbnb refunded all our money. (There was also an airbnb in Fez which advised us to hire a guide to tour the medina and the guide turned out to have ulterior motives but that’s another blog post.) Most nights in Morocco we found cheap hotels (averaging less than 20 euros a night) in whatever town we ended up in. But it was in Morocco that we did our first workaway and this experience turned out to be the highlight of our trip. Workaway is an online community bringing together adventure-seeking travellers with people looking for help with work projects or interesting activities. It’s like WWOOFing (World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms) but it’s not just work on farms. It can be anything. In exchange for doing some work the traveller gets free room and board. Some examples featured on the site include : “Help Family Run Hostel in Greece”, “Help at a Community School in Nepal”, “Help Build Eco-House In New Zealand.” You could spend all day on this website dreaming about your next trip. While I was planning our trip, I didn’t expect to see any workaway offerings in Morocco, remembering how otherworldly and ancient much of the country was from my two previous travels there, so was surprised when I found that even this relatively new website had reached North Africa. One workaway posting came from an American family who’d moved to the coast of Morocco and needed help building their house. That didn’t sound that culturally enticing so I kept searching. Finally I saw one posting that really stood out, mainly because of its rave reviews. It scored 100, meaning that everyone who’d stayed there had given the Berber House the highest possible score in every category. I contacted the owner Mohamed and he said he’d be delighted if we came. We just needed to get to a town called Imantanout in southern Morocco. A month later we found ourselves inside an unmoving ramshackle bus at the noisy chaotic Marrakech bus station, waiting for the bus to fill with enough people to take us to the little Berber town of Imantanout. Even though we had to wait three hours before the vehicle moved, it was preferable to what we’d gone through before getting on the bus, where we’d been swarmed by shysters trying to sell us dubious bus tickets. A few days earlier, Rob’s wallet had been pick-pocketed in northern Morocco and we were harbouring bad feelings about the country. By the time we finally reached the little Berber town of Imantanout near dusk we were frazzled and bus-weary. The place where the bus dropped us off was dirty and crowded. We needed wireless to contact Mohamed and couldn’t find it anywhere. “This is all too hard,” I blurted out, looking at the crowds of men in their djellabas and skull caps, many of them staring at us, the only non-Moroccans in town. “I don’t remember Morocco being so difficult when I was here before. Let’s just go to this workaway place for a couple days and then get out of here, go back to Spain.” Rob and Quinn agreed. Everything changed an hour later when we came across a central square full of people and cafes off to the side. I found wireless and Quinn played soccer in the square, soon joined by a gaggle of kids. Mohamed came to pick us up and drive us to his tiny village in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains and that’s when we realized what all those travellers had been raving about. The Berber House is Mohamed’s own house where he lives with his extended family. We entered the expansive leafy open-air courtyard, the heart of the house filled with comfortable couches, tables and books. The first person to greet us was Mohamed’s two-year-old daughter, an expressive little imp who within minutes of our arrival jumped into my arms, looked at me with huge brown eyes and initiated a high five. After the hassles of northern Morocco, arriving at the Berber House felt like gulping spring water in a desert. We couldn’t believe our luck. Soon, a young woman named Julie came out of her room. (Guests and the family stay in simple rooms off the courtyard.) “I thought I heard Canadian accents out here!” she exclaimed, shaking our hands. Julie was from Thunder Bay and had been travelling on her own for over a year, staying mostly at workaways around the world. She and I immediately hit it off. Then out came Mireia from Barcelona but living in Ireland. Again, another instant travelling soul mate who I could spend hours talking with. (Coincidentally, Mireia happened to be reading a book of women’s travel stories in which I’d contributed. Small world!) Then Angela from Boulder and California appeared. Same instant connection. While I was talking to my new friends, Quinn was learning a soccer trick from a young German guy named Nico. Rob was talking to a fun couple from North Carolina, Veronica and Hunter, who sold their house to travel the world. When they’d almost run out of money in Italy they realized they could go home and start working again, or keep travelling but only do workaways. They decided to keep travelling, mainly doing workaways which focused on eco-building. Best of all we got to meet Khalid, Mohamed’s sweet funny twenty-something relative who over the next week would take the group of us on outings to integrate us into Berber culture. How could this Shangri-la be a workaway? What was the actual work we’d be doing? It turned out to be the off-season for the Berber House’s olive grove so rather than working we would pay a small fee for our room and board. The owner Mohamed truly just wants to introduce people to the lovely gentle lifestyle of the Berber people. Some of the things we got to do with Khalid that week were hiking to a remote nomad market where we all ate breakfast inside a tent surrounded by dozens of Berber men drinking mint tea; hiking up a mountain to a cave; visiting a hammam (public bathhouse) where a woman scrubbed the layers off our skin while unselfconscious naked Berber women chatted around us; visiting a school where I was happily swarmed by giggly little girls who played with my hair and sang to me; learning to make proper mint tea, bread and tagines. Khalid even showed us a mind-boggling card trick which had us all stumped for hours. The best part was the bond we all formed in spending every day together, telling travel stories, and laughing. I hadn’t found a place like this in years, maybe not since I stayed at the remote beach campground on the faraway little island of Taveuni, Fiji (which I wrote about in my first book, Kite Strings of the Southern Cross.) I find that when places are difficult to get to—sometimes taking several days of hard travel to find—that’s where you come across the people you could be friends with for life. You belong to the same tribe. For example, you only learn about the Berber House if you sign up on workaway—which only appeals to a certain kind of person—and you must have the fortitude to forge through aggressive northern Morocco and have faith things will get better as you head deeper and deeper into the south. Those obstacles alone filter out the vast majority of people from ever reaching the Berber House. The few who make it there are sure to have a lot in common. And have a lot of fun together. Although we wanted to stay forever, we had to push on since we still had so much to see in our month-long trip. Our new friends from the Berber House left the same day, heading east while we headed southwest toward the Sahara Desert, to a village we never would have learned about if it hadn’t been for a traveller at the Berber House. The Sahara Desert also took days of hard travel to reach—and was stunningly, impossibly beautiful—but since we came across few other travellers there, we never made friends like we had at the Berber House. The third website that was central to our trip was blablacar.com, a European ride sharing website which we used in Spain. Drivers offer rides to wherever they’re going, and people who need rides type in where they want to go, see who’s driving there, then connect with the driver. It’s fun to meet people this way and much cheaper than the bus or train. If you’ve found any websites that have enhanced/hindered your travels please comment (or feel free to comment about anything else!) I’m one of those people who often finds herself getting talked at. People talk at me because I listen to them. I can’t help it. I’m fascinated by people. I want details. I want gore. I want to know what your aunt said at those Mayan ruins to provoke her second husband to leave her for good and fly home alone from their Mexican honeymoon. This penchant of mine, I suppose, might be why I’m a writer. Listening is one of those skills we writers need. We spend our days listening, observing, ruminating, storing things away.

But this kind of one-sided listening can only go so far. No matter how entertaining someone is, if he or she does all the talking and no listening, the listener starts to wither inside. When people fully dominate conversations, no matter how riveting their stories, our energy is sapped. People who are unable to listen are lonely because they don’t truly know anyone (nor can they know much about the world or even life itself.) We’re wary of these non-listening talkers. We cross the street to avoid them. The talkers don’t realize that when they’re doing all the talking, we diminish in their presence. We slump in our chairs and feel uninteresting and depleted. Think of when people laugh at your jokes and you keep getting funnier and more animated. But when people stare blankly at you, the jokes die. It’s the same principle. So we must learn to listen. I believe listening is a great gift we can give each other. Listening to people makes them feel energized. The act of listening encourages people to release what’s buried deep inside. In essence, when we listen fully to people—focused eye contact, nodding, really listening intently—we are cheering them on to express their true selves, to come to an understanding of who they really are. When we are eagerly listened to, we unfold and expand, creating more of ourselves as we talk. Ideas and revelations start to grow within us and come alive. Listening is a powerful and creative force. I remember once telling a group of friends a story about something that happened to me in my 20s on a Greek island—something vaguely supernatural that I’ve still never really been able to explain. As I told the story, I noticed their faces changing. They’d set down their wine glasses and their eyes were wide. “Why haven’t you ever written about this?” They were incredulous. My first book about my life as a traveller had just been published. I hadn’t even thought to write about this Greek adventure until I told them the story that night. Talking and listening to each other is good training for writing. When we tell stories we see firsthand what people find compelling, which parts of the story have the most energy. Sometimes when I tell a story, people surprise me by being curious about something that I hadn’t thought was especially significant. They press me for more details. This is useful later when I write the story. Listening is also a way writers can help each other find new directions. “You should write about that!” is something writers need to say to each other often. As I go through this life, I notice some people are lousy listeners. For some reason it always surprises me. A real conversation is like an alternating current that recharges both parties. A one-way current eventually burns out whatever is on the receiving end. (Actually, I’m not sure, electronically, if that really happens, but it certainly happens in the situation of chatterboxes who can’t shut up. On the receiving end of these people’s onslaught, we the listeners are fried.) In this new year I encourage you to avoid people who don’t listen and instead, seek out friends who you can’t wait to have an inspiring two-way, thought-provoking, mind-expanding conversation with, where you give each other the gift of listening. Then transform what you learned into writing! When I was halfway through writing my first book many years ago, I remember reading in Bird By Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, by Anne Lamott, that the best part of being a writer isn’t getting your name in print. It isn’t all the excitement and accolades that accompany being a published author. The best part of being a writer, she said, is the writing itself. Damn, I thought. Writing is such hard work. How can that be? A year later, I realized she was right. The writing is the best part. The writing is what energizes and enriches me, deepens my life in more ways than I can count. Once you’ve finished writing your book and it’s in the hands of others—publishers, editors, the media, readers—you’re no longer behind the wheel, taking your characters places they need to go, deciding which verb conveys exactly the right mood, letting the phases of the moon dictate how the night sky looks. Once your book is out in the world it’s no longer yours. The publisher might even change the title on you, as my first publisher did. So the writing itself is what I always go back to—sometimes kicking and screaming and dragging my heels—but before long, I remember why I write: it makes me feel good. I feel an inspiration starting to grow, an image I can’t shake, an emotion or idea that desperately needs sculpting into words. Sometimes I don’t even realize I’m feeling a certain way about something until I start writing about it. Someone once wrote, “How do I know what I’m thinking if I haven’t written about it?” I get this. I need to write whatever I’m feeling strongly about for the ideas to take shape. Writing organizes my thoughts and sets free my feelings, ideas and opinions. Even if nobody ever sees what I write, it doesn’t matter. It’s still liberating. It still invigorates. I love the feeling of transforming something from my own experience and sending it out into the larger world, writing about something that while personal is hopefully also universal, an experience that might induce others to nod in recognition and feel less alone. Writing is immensely cathartic. What was interior becomes exterior, and when it’s exterior it’s tangible, made more real. Writing lets me live parts of my life over again, even the painful parts. The second time around I can re-examine and reflect, work out why I took one particular road in life over another, attempt to recall who I was in the past, what I thought, and wonder if a part of that younger me still exists. Writing forces me to observe life in detail, to live in the moment. I find that my two passions, writing and travelling, feed off and enrich each other. When you’re on the road, everything around you takes on a vibrancy you may not have experienced since childhood. When you’re in a new place, you absorb fresh life around every corner; you see everything from a crooked angle. Time stretches and your senses sharpen. In other words, you’re paying attention. And paying attention is a writer’s job. If you intend to write about what you’re seeing, you’ll be even more aware of the details of the moment. You’ll look more closely, listen more clearly, taste more carefully and continually reflect on what you’re experiencing. All your senses are heightened. As a result, your writing—and your travels—will be deeper and richer. Writing also gives me a sense of accomplishment. I taught school for years and I don’t think I was very good at it. I’m terrible at any kind of retail job— unless I can read a book behind the cash register. I’ve probably had over 100 jobs in my life and although some have been fun, nothing has suited me like writing has. Writing, although hardly a profession that pays much these days, has in many ways saved me from being an aimless wanderer. It roots me to solid ground. What I have not earned by way of money is more than compensated for by wealth of experience. Writing has shaped me as a person in a way no office job could. But above all, writing gives me redemption. If I write about an experience I can lift it up to another level, helping me and my readers understand more about the world. I thought about this recently when writing my latest book. It’s not a travel book, but it discusses a terrifying journey nonetheless. Writing about how my son developed Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in reaction to his grandfather’s death made me consider how writing about a difficult and traumatic experience can bring out the truth of who we are. What we find out about ourselves is not always pretty, but it’s real and it’s human. *My post above also appears in this month's QWF Writes (the Quebec Writers' Federation blog)  Springsteen in Pittsburgh, 2014, High Hopes tour Springsteen in Pittsburgh, 2014, High Hopes tour It was getting dark and I had just arrived at my first-ever airbnb.com homestay—airbnb is an online community where you can book a place to stay at someone’s house, or rent out a room yourself. It’s a step up from couchsurfing.com since you pay to stay, but places are generally much less expensive than hotels. And more personable. The place I’d chosen was out in the country, a miniature Victorian village of tiny buildings constructed on a woman’s farm, eight miles outside of Ithaca, New York. It was C$32. From the photos, Karenville—named after the owner—looked exactly like the kind of eccentric, laid-back, friendly sort of place I wanted to spend the night. I was on a solo road trip—a birthday present to myself last month—on my way from my home in Wakefield, Quebec, to Pittsburgh, to see Bruce Springsteen the next night. Staying in hotels didn’t appeal. Airbnb and Karenville did. Except as I looked around I realized this place looked nothing like Karenville. I was on a lonely country road, parked in the driveway of what looked like a regular farmhouse, no miniature Victorian village, and no Karen—shown in her profile picture to have long silver braids and lots of animals. I re-checked the directions that google had given me on the airbnb site. I had the right address. I tried knocking on the door of the farmhouse but nobody was home. Finally, a car pulled up and an elderly couple with some grandkids in the back eyed me suspiciously. “Who are you?” said the woman, rolling down the window. I explained my predicament. It took them a few minutes to warm up to me and believe my story, but after seeing the address on my ipad they were convinced. “Looks like you’ve been scammed,” said the man behind the steering wheel. “There’s no B&B anywhere around these parts. I’ve lived here all my life. Never heard of this woman, or a miniature village.” He chuckled. “Did you pay her already?” asked one of the kids in the backseat. “Yeah, I did, through paypal.” “Well you can kiss that money goodbye,” said the woman, shaking her head in a way that showed her disgust with the depravity of the modern world. “But Karen seemed so nice,” I said. “And the place seemed real. Look at all these photos!” I held up my ipad again. They didn’t know what else to say and I sensed they wanted to go inside now that the excitement was over. Feeling dejected and confused I drove back to Ithaca. Just an hour earlier I’d eaten at the Moosewood Restaurant and had wandered around the pretty town, watching students and parents getting tours of Cornell. Now back in town, I found a Starbucks with wifi, found Karen’s contact info and sent her a message through the airbnb site: “What’s going on? I went to the address and it wasn’t Karenville. Are you real?” Karen wrote back immediately. “Yes! I’m real! Google maps refuses to give my proper address on the airbnb website. It must be because we’re off the grid and kind of hidden. Sorry about that! Come back and go a further quarter mile down the road. My husband will meet you out there with a flashlight. We don’t have electricity and it’s dark.” Except for the correct address, which is rather crucial, Karenville turned out to be everything Karen claimed it was on the website: a rustic, tiny, off-grid ‘village’ where you can stay in an old-fashioned ‘hotel’ that’s ten by ten. Karen’s husband gave me a tour the first night of all the buildings, each one like a dollhouse for grownups. The next morning Karen told me about her frustration trying to get airbnb to give the right address to her guests. I also tried to contact them about this but got frustrated myself when I realized there is no ‘Contact Us’ page. For such a huge company—serving 192 countries and reportedly worth ten billion dollars—this is shocking, and arrogant. After saying goodbye to Karen, I stopped by the farmhouse of the old couple to let them know that Karenville is, in fact, real, and just a quarter of the mile down the road. My next airbnb stay was in Pittsburgh, in a treed neighbourhood of old houses and spring blossoms on the boulevards. First, I’ll tell you about the concert. You can skip ahead if for some reason you don’t know about Bruce Springsteen and the energy he generates wherever he goes. The Springsteen concert was fantastic, as always. Whenever I’m in the midst of one of his concerts—dancing, singing along, trying to take it all in—I’m on such a high that I sometimes feel that if I died right after that would be okay; I could go out on a high note. "The band played their usual thrilling, high-octane, three-and-a-half hours, and when they finally left after the last song, Bruce Springsteen didn’t." On the afternoon of the concert in Pittsburgh, I’d made friends with some fellow fans as we’d lined up to try and get ‘pit’ tickets (where you can be right in the very front as opposed to just on the floor) and I was with the same people again at the concert—a fun Pittsburgh couple, and two cute young lawyer guys who turned out to be from Toronto. While waiting for the concert to start, we’d discussed Rob Ford, Toronto’s most interesting neighbourhoods, Downtown Abbey, and other concerts we’d been to. The five of us ended up becoming fast friends, hanging out and dancing together throughout the show. The band played their usual thrilling, high-octane, three-and-a-half hours, and when they finally left after the last song, Bruce Springsteen didn’t. He just stood there by himself, hesitating. He didn’t seem to want to leave the stage. “What’s he doing?” people asked. The lights were on and everyone seemed to be holding their breath. Then Bruce walked over to an organ, sat down, and started talking as he noodled around on the organ keys. You could tell this wasn’t rehearsed. Everything he said was off the top of his head. He said he realized he’d been playing the guitar for almost fifty years. Fifty years. He couldn’t believe this. He talked about how much music had meant to him, how it had saved his life. Then he said if it wasn’t for us, for his fans, he’d be nothing. He wanted to thank us, to “thank us for showing up so often.” “You’ve added so much to my life,” he said, as if he couldn’t believe his luck. I was thinking, Geez, you’ve added so much to our life. You could tell he meant every word he spoke. Then he sang a couple of songs. It was probably the most genuine heartfelt moment I’d ever witnessed in a public space. Now back to airbnb, not nearly as interesting: I got horribly lost trying to find my way back to my airbnb place. The woman who owned the house where I was staying had kindly printed me out directions the night before to get to the concert downtown. I figured all I had to do was backtrack to get home. But no. The main road I’d come in on was a one-way street. I ended up in a dodgy neighbourhood at midnight asking directions at a gas station where the girl behind the counter was behind bullet-proof glass. When I finally got back at 1 a.m., I worried that I was waking up the home owner and her boyfriend. We all shared a bathroom and my bedroom was right next to theirs. Then at 6 a.m., they were the ones who woke me up with what was either a blender, a hair dryer, or a stealth bomber in their kitchen. Clearly, this was another drawback of airbnb. It can be a little cozy. But for fifty dollars, I wasn’t complaining. My bedroom was lovely and had a cushy bed. At the last minute I decided to book a final airbnb at the half-way point. There was no way I could make the ten-hour drive home on five hours of sleep. Although, again, I got ridiculously lost roaming around the Rochester suburb in search of this last airbnb place (I really need a GPS!) when I finally found it, it was perfect. The friendly, twenty-something owner of the little bungalow had cleaned up her craft room for me. The bed in her craft room was a luxurious retreat of duvet heaven and I slept ten hours straight. It cost $30. Overall, I’m so impressed with airbnb (except for their lack of a Contact Us page) that I might try renting out our tent trailer for some summer nights, right in our woods in Wakefield. Thirty dollars for a night including a vegan breakfast? I’ll just make sure the address is right. Click here for my blurb and video on Springsteen's Born To Run: Top 40 Travel Songs of All Time (Worldhum.com) My random taste of Bruce Springsteen video below (all footage by Laurie Gough)  Oh God, we’re going to be stabbed or kidnapped, probably killed. Certainly robbed. This is what I get for being cheap. These were my thoughts as I sat in the back of a scruffy taxi several nights ago in Mexico City. Beside me sat my eleven-year-old son Quinn and in the front sat my husband Rob next to the taxi driver. A few moments before, back at the bus terminal, we could have taken one of the safe ‘securidad’ authorized taxis to our friends’ place. But no. Those taxis were more expensive, and besides, we’d already taken regular taxis off the street in Mexico City and they were perfectly fine. As were all the taxis we’d just been taking the past month in Oaxaca, along with all the local buses. The vast majority of Mexico, I was always saying to friends, is safe. Being afraid of a place like San Miguel de Allende, or anywhere in Oaxaca, is like being afraid of Ithaca, New York, or Brattleboro, Vermont, just because there are murders in East L.A. It’s buying into the media’s ridiculous hysteria of a dangerous Mexico. But perhaps Mexico City was a different story. Especially since this twenty-year-old taxi driver, who claimed he knew exactly where our destination was—Polanco, a nice neighbourhood half an hour away—obviously didn’t have a clue where it was. Or maybe he did know but it was irrelevant since his real goal was to take us to an ATM at gun point. After leaving the bus terminal, he’d driven three minutes down a main thoroughfare, did a U-turn, drove back the same way, then called someone on his phone as he roared down the road. Next he stopped at a gas station and this is where I got suspicious. I didn’t see him get any gas, although Rob thought he had actually stuck the gas hose in for ten seconds. Rob didn’t seem worried in the least. Then again, he wasn’t a seasoned traveller like I was. And he hadn’t read about Mexico City Taxi Driver Kidnappings. Rob is laidback. I am too, usually, but not when a taxi driver in a dodgy taxi is making frantic phone calls while driving—probably to his criminal conspirators—and now, Jesus Christ!—actually talking to a scary-looking guy in a black car at the gas station. “What the hell is going on?” I said to Rob. “This doesn’t look good. Why is he talking to that guy? Does he know him? Are they friends? His friend just happens to be at the same gas station at the same time?” “I’m sure he’s just asking the guy for directions, relax,” said Rob. How could I relax in this situation? And now that we were back on the road, the scary guy in the black car was following us. After five minutes, our driver turned off and careened into a dark alley. Really dark. Deserted. He stopped the car and got on his phone again. The guy in the black car was still behind us in the alley. I was planning our escape, my heart pounding. “Should we get out now? I whispered. “Just leave our bags in the trunk and run for it?” Quinn seemed to think this whole thing was funny and hugely exciting. Rob just thought it was funny, which I found incredibly naïve. When the taxi driver got off the phone I pointed at the guy in the black car behind us and said, “Tu amigo?” Your friend? That would show him I was onto him. He answered no, but I didn’t catch the rest. My Spanish isn’t that great and he was mumbling, probably not wanting to give away the illicit details of the imminent crime. Then we were driving again, back onto a highway, then another, then another, for many miles. The guy in the black car was still behind us. I knew it was the same guy because I kept asking Quinn, and Quinn is a car geek. He knows the make and model of every car ever made. All I recognized was the car was black and old-ish. After that I wouldn’t have had a clue. “Rob, this is bad. We're still being followed. And why is he on the phone again?” “He must be getting directions. Do you really think if he was going to rob us he’d have wasted this much gas? If he was going to kill us he’d have done it already.” “Oh, you do have a point.” Half an hour later we were still driving, but we’d now lost the guy in the black car. Earlier, I’d recognized a sign for the anthropology museum so knew we were close to the right neighbourhood, but twenty minutes had gone by since then. We really were lost. The guy didn’t have a clue where he was going. On the bright side, I was starting to relax about him murdering us. Then, things started looking familiar. Suddenly, I recognized our friends’ street. “Aqui!” This is it! The taxi driver looked positively gleeful. We got out and collected our bags and I considered kissing the pavement. I was so relieved not to be dead in an alley, and so grateful to the sweet young taxi driver who’d gone to so much trouble to find the place—even eliciting the help of a random stranger at a gas station (who was that nice guy in the black car?)—that I paid the driver more than what the authorized taxi would have cost. He looked confused when I told him to keep the change, then flashed me a huge grin. “How did you know he wasn’t going to do something horrible?” I asked Rob after the driver drove off. “Because I could see him texting his girlfriend. He kept sending her heart emoticons and she was sending them back. You don’t send hearts in the middle of criminal activity.” The moral? Don’t be too hard on Mexico. Or its lovely citizens. by Laurie Gough ************** For more on Mexico, see my previous post, Ten Things You Probably Don’t Know About San Miguel de Allende Stay tuned for my upcoming post on our adventures in the state of Oaxaca.  Quinn and author at top of Imperial Lift in Breckenridge, 12, 840 ft. Quinn and author at top of Imperial Lift in Breckenridge, 12, 840 ft. It seemed like an overly ambitious and vaguely absurd idea to take my eight-year-old son on a week’s ski vacation to Colorado. After all, he’d only skied five days in his life and that was on low-lying rolling hills, not mountains. Since it was just the two of us going to Colorado and I wouldn’t be able to leave him alone, I imagined spending the entire week on the bunny hill while I gazed way up at the sky-piercing powdery peaks with longing. But this is something I learned that week: when it comes to skiing, kids are weirdly fearless. Sure, my child, as it turned out, isn’t brave about making small talk with friendly seat-mates on chairlifts—my chatting with strangers seemed to cause him so much embarrassment he’d freeze solid, staring ahead as if he didn’t know me—but the skiing part he tackled like a Swiss downhill racer on speed. No anxiety at all. I supposed this lack of fear in kids has something to do with them being closer to the ground than adults. But more than that, I believe it’s sheer naivety. They don’t know they could tear a ligament, or slip off an overhang unnoticed, or lose a whole finger. They don’t know they could be trapped in a snow bank until the spring thaw melts them into floppy carcasses. They haven’t lived long enough to figure these things out. After the first half-hour on the bunny hill beside One Ski Hill Place in Breckenridge—the resort having the advantage that you can simply walk outside and step onto a chairlift—Quinn announced he was ready for the high mountains. “But this is the best bunny hill I’ve ever been on!” I told him. I was enjoying being ferried up the slow-moving sidewalks to the top of the hill and working on my turns going down. So what if I was surrounded by pre-schoolers. It was a blast. “Mummy, this is boring!” he pleaded. I grudgingly agreed we’d try one of the mountains, but seeing how high they were, I worried that once we made it to the top, he’d be too afraid to come down. “It’s a long way up there, might take an hour,” I told him, “and the mountains are full of five-foot moguls.” “Awesome!” he squealed, punching his fist in the air. The first chairlift we rode took in sweeping views of Breckenridge’s myriad ski runs, endless long white ribbons cut into forests of the deepest green. Below, we watched jovial families skiing in multi-coloured ski garb calling out to meet at one restaurant or another; Argentinean sixty-somethings racing with helmet-cams; and snowboarders practicing their Shaun White jumps on special snowboarding ramps. Finally, we neared the top. “OK, we’ll be de-chairing soon,” I said, apprehension in my voice. Giggling at my airplane joke, he flipped up the bar as if this were a kiddie amusement ride, and proceeded to hop from the lift down to the ground. “How did you know how to do that?” I asked, bewildered, as if someone must have kidnapped him in the night to show him what I remember being a terrifying ordeal when I learned to ski as a teenager. “I watched the people in front of us,” he shrugged. “Oh,” I said. But he didn’t hear me. He was skiing toward the nearest mountain edge along with the crowd. “There’s a green run over there,” I shouted out after him, meaning the colour-coding system to classify how difficult the slope is—green being easy; blue being not so bad; and black being yo is dead! He obliged to take an easy green, one called Snowflake, but complained the whole way down that it felt more like cross-country skiing, a lot of hard work. Clearly, at 55 pounds, he was too light for Snowflake. On the next run, and the rest of that day and the next, we skied down blues together and I thought we’d hit our stride, our comfort zone for the rest of our skiing lives together contained in the colour blue. On those blue runs of Breckenridge, especially on the back bowls, I felt an exhilaration I hadn’t felt skiing in years, laughing nonstop with Quinn as we glided from one valley to the next, often having an entire blinding-white paradise of a mountainside in the sun all to ourselves. But on the third day, some snotty-nosed ski brat standing behind us in a lift line bragged to his friends about having just gone up the Imperial Lift, the highest chairlift in North America. Quinn wanted to try it too. “But we like the blues!” I said. It was futile. His face was too excited for me to refuse. Soon, we found ourselves at the highest elevation we’d been yet, and about to ascend further up a t-bar tow with a warning sign that read, “Experts Only Beyond This Point”. We went up anyway. We could always walk down if we had to, I reasoned, swallowing my panic. Next we rode the Imperial Lift itself, which catapulted us above the tree-line into an Arctic climate, an entirely different weather system than down below. Down below, we’d barely needed our jackets in the sun. Down below, people were drinking beer in t-shirts on outdoor patios, getting tanned. Up there, wind whipped our faces raw as we stepped off the lift. We spotted an elevation sign: 12, 840 feet. I was surprised we didn’t have altitude sickness. I gazed around the mountaintop. It felt the way Everest must feel, a low persistent howling, thin crisp air, frozen dead bodies scattered around. I realized the only way down was a double-black diamond run. Not single black, but double black. “Let’s go!” shouted Quinn. He took off like a baby snow leopard chasing a tumbling rock. I watched in horror, the way one does when her offspring disappears down a cliff, but then, realizing he was skiing just fine, I ignored him to confront the sheer icy descent on my own. Criss-crossing the entire mountainside in dozens of near-horizontal back-and-forth lines, it took me half an hour just to get down to the Imperial Lift. Unlike my son, I understand about comas. Quinn, who’d been patiently waiting for me, wanted to go again. It was getting late, so I talked him into going back to the bottom and drinking peppermint hot chocolate instead, and maybe later, going bowling at the lodge’s mineshaft-themed bowling alley. His face lit up and he agreed. He may be an expert skier, but he is, after all, still a kid. Laurie Gough *Note--This story was slated for the Toronto Star but the editor just told me his freelance budget was slashed and he couldn't publish stories he'd agreed to after all (not his fault; it's just the general state of things these days with the decline of print media). So I thought I'd stick it on my blog instead. Quinn is a bit older now and once he gets off his crutches, will start skiing again. (I'm actually not joking!) |

Laurie GoughI'm an author of books about my travels, a freelance writer, an adventurer, a mother of a little boy, an environmental activist, and someone who daydreams about finding the perfect place to live. Archives

September 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed